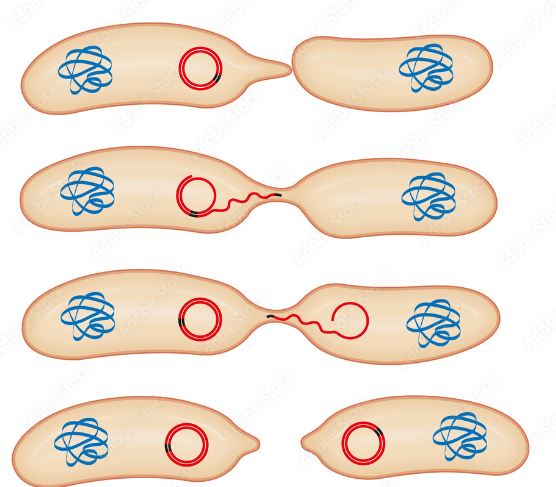

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the aquatic environment is a hotspot for the production and transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). This is due to the contamination of receiving water from agriculture practices, wastewater treatment plants, and human waste. Biofilms form in drinking water pipes and create an ideal environment for vertical/horizontal gene transfer of plasmids containing ARGs. Plasmids replicate independently to chromosomal DNA and can even incorporate the ARGs into the genome of surrounding bacteria via pili. This is a big problem because if antimicrobial resistant bacteria enter the human gut via drinking water it can transfer ARGs to your gut microflora. Once your gut microflora has the ARGs incorporated it becomes harder to fight off pathogens since the gut microflora can transfer the ARGs into the pathogen. Now you have a pathogen with AMR that didn’t previously have any making it harder or even impossible to treat resulting in over one million deaths in 2019. Chlorination is used to try and keep drinking water clean, but studies have shown that it can increase the abundance of plasmids with ARGs. In developing countries with high fecal contamination or no regulation of antimicrobials are more at risk to AMR exposure. Very problematic ARGs have been found in plasmids all around the world such as the blaOXA-48 and blaNDM genes in Canada. These genes have resistance to carbapenem which is the last line of defense used to treat MDR infections such as pneumonia and meningitis. There are many different ARGs carrying plasmids in bacteria all over the world each with different genes and resistance to different antibiotics. Although plasmid-mediated AMR has been identified as a huge problem it still isn’t included in the guidelines for water quality. Not only is it not being screened in water quality tests, but there is also no standardized way to identify ARGs and ARB as contaminants in drinking water and this articles goal is to find a test for these. It isn’t difficult to identify ARB in a lab and a culture-based method can be used by plating bacteria isolated from drinking water onto agars supplemented with antibiotics. This isolates the ARB but only for a specific resistant profile which could give false negatives depending on what antibiotic is used and underestimates how many strains of bacteria could be in the sample. You can also do a total genomic DNA extraction to investigate any plasmids present via alkaline lysis, but you would also need a lab and prior knowledge of sequences is needed for PCR. Another alternative is the exogenous isolation method which captures plasmids directly from a sample of drinking water. This method uses a plasmid free E. coli with a selective marker and rifampicin or kanamycin resistance. These E. coli are then mixed with the water sample which allows for horizontal gene transfer from the ARB to the marked E. coli. Then the bacteria are resuspended on selective plates to see if the marked E. coli took up a plasmid or not. This method doesn’t identify the plasmid host, but it does identify of plasmid-mediated AMR (PMR) takes place in the drinking water. Since the problem is most prominent in developing countries, the tests need to be easy to perform, cheap and accessible to everyone. The exogenous isolation method is currently the best way to identify PMR bacteria since you don’t need to know anything about the ARB in the sample and it tells you if there is PMR or not. This test still doesn’t solve many problems because once you conduct the test and determine if ARB are present you will have to boil it which you could’ve done prior to the test. It also only captures plasmids that can be transmitted to other bacteria and there are still mobilizable plasmids that could eventually get introduced into your gut microflora. This could cause more harm than good because you might think that the water is safe to drink so you don’t boil it allowing the mobilizable plasmids to infect you so it’s best to just boil the water if there are doubts. This is an area of emerging concern and there are not enough studies to know the amount of ARB/ARGs in drinking water. This article highlights the need for increased research into PMR and understanding how to access our drinking water. The best thing to do with the current understanding of PMR is to start providing exogenous isolation tests to people and see if the number of infections is reduced.

Source https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666765722000278#bib0031